Blast from the Past: This entry posted initially on July 10, 2016 and was reposted on June 18, 2022. This blog explores how to teach an aspect of reading comprehension that most teachers have no idea how to teach. It provides an example drawn from the Common Core standards. This might seem out of date since some states have withdrawn from those requirements (or were never part of them) – however, I did a quick check of the states that have made a big deal of not having CCSS standards… all of them (e.g., Florida, Texas, Virginia, Alaska, Nebraska, Arizona, Oklahoma, Indiana, South Carolina) require the teaching of theme in literature. That makes this blog as important now as it was then -- all 50 states require teachers to teach kids to identify theme in literature. However, these days more and more teachers are buying into the idea that knowledge is the key to reading comprehension and are failing to teach kids how to do things like think about and analyze literature. Big mistake – and one that runs counter to the “science of reading.” The instructional approach described here is very effective across the grades. Give it a try and you'll see what I mean.

Many years ago, my daughter, Meagan, had a homework assignment. Her literature teacher assigned a short story to read and Meagan was to figure out the theme.

The theme she came up with: “People do a lot of different things.”

Needless to say, it doesn’t matter what the story was, that wasn’t the theme. (Though she was a little surprised that I could know that without even reading it.)

“Meagan how do your teachers teach you to figure out theme?”

“That’s just it, Dad. They don’t. They tell you what a theme is and I know what a theme is, and then when you get the theme wrong they tell you the theme and that is supposed to help you next time. But it doesn’t because that story has a different theme.”

My goodness...the same method my teachers had used with me!

Practice alone is not likely to teach kids to identify theme. The same could be said for other comprehension “skills.” No matter how often you are asked to do them, you still won’t be able to without some instruction.

That’s a problem in lots of schools. Reading comprehension instruction has to give kids opportunities to read and to use the information: to answer questions, to discuss, to source one's writing. But there has to be more to it than that. Instruction should help kids to think about that information more effectively; to remember more if it; to analyze it more deeply.

Reading practice is important. But practicing what you don’t know how to do is nonsense.

What got me thinking about that was a review of the Common Core standards for reading. Look what kids are supposed to do with theme by high school graduation: “Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text.”

Man, if we aren’t going to teach kids how to figure out one theme, how will they ever know how to identify multiple themes?

I did a quick review of books for teachers on how to teach reading comprehension. It is interesting because, if they mention theme at all, they usually only define it and give some examples. In other words, the same instructional method Meagan described.

In good literature, the characters change across the text; the so-called “arc of development.” Wilbur is a different pig by the end of Charlotte’s Web; and the Elizabeth Bennett at the denouement of Pride and Prejudice is not the same acerbic Lizzy that we start with.

Kids who can’t tell you a theme, can usually track the changes the characters go through. And, they can tell you whether those changes are good or bad.

Theme is wrapped up in those changes—and because the best literature tends to have multiple multi-dimensional characters—characters who grow and learn—a story might have multiple themes. That's what Joanne Golden and John Guthrie reported in 1986 (Reading Research Quarterly). The kids may empathize or identify with one literary character, while the teacher focuses on another. Then, when the kids identify the story theme based on the character that drew their attention, they get graded down for interpreting the text differently than their teacher.

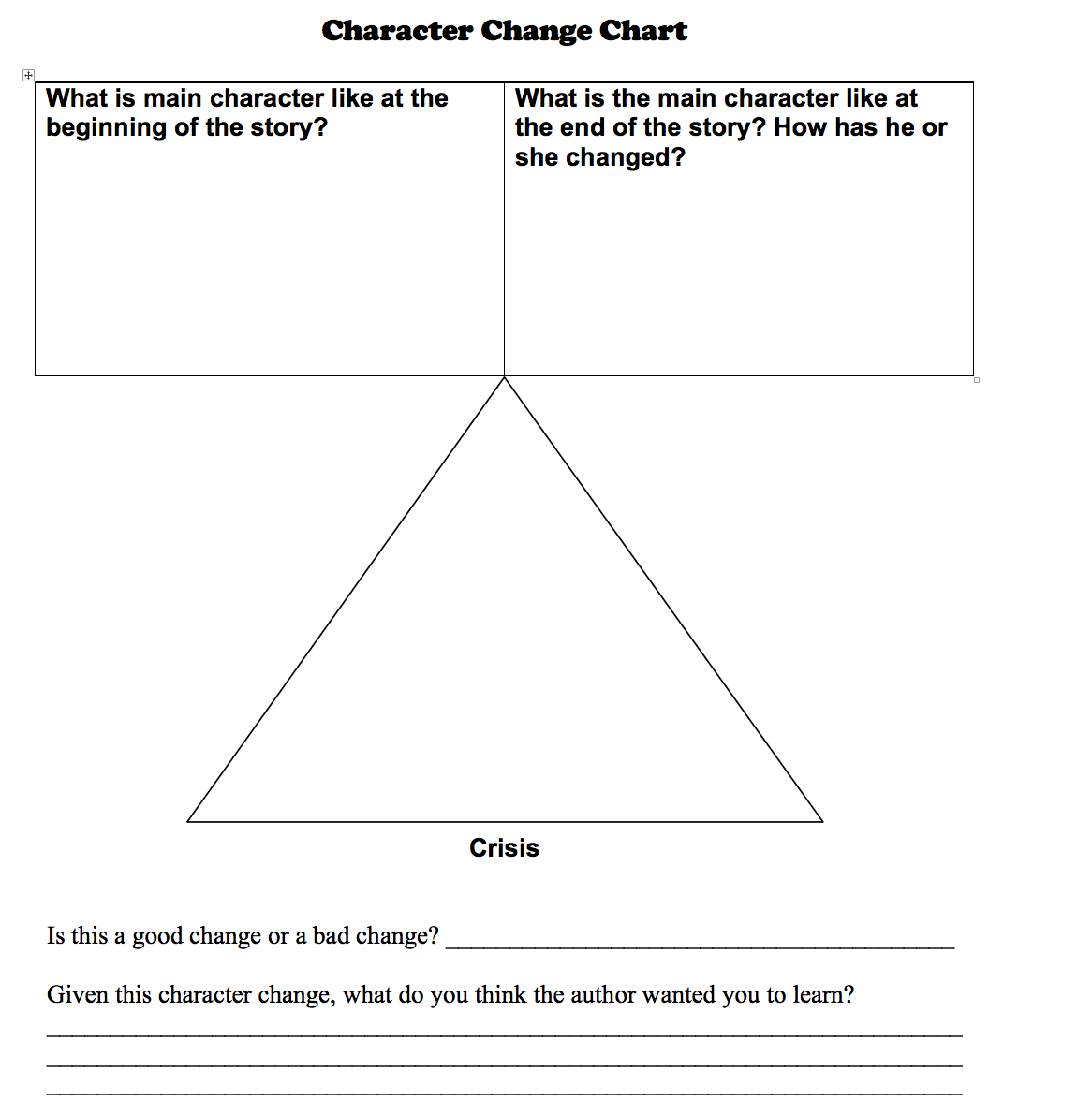

We need to teach kids to track character changes across a story, to evaluate the value of those changes, and then to construct a potential lesson or theme based on that information.

Once kids know how to do that, practice is a really good idea. Before they know how to do that, practice can’t help much.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.