Teacher question:

In the current era of readily available teacher-created materials through open marketplaces, and given the critical importance of print materials for beginning readers—particularly for multilingual learners and students with disabilities—what does current research indicate are the best practices regarding the optimal amounts of extraneous visuals to truly support their literacy development effectively?

Shanahan responds:

I hope most teachers are not spending a lot of time “creating” instructional materials. Some do, of course, but they tend to be a tiny minority. I’d rather their time be spent on figuring out students’ learning needs.

Of course, there are those cut-and-paste artists who create “new” materials by photocopying other people’s work (there’s plenty of that on Teachers Pay Teachers). I wouldn’t want to encourage that kind of thing.

On the other hand, teachers do, themselves, purchase materials or serve on curriculum selection committees that make those choices. The kind of information you requested could be of value to them.

My main interest is with how we can best teach children to read. Accordingly, my answer is aimed at guiding teachers about how to work with pictures in reading instruction. I’ve written before about that kind of thing when it comes to science reading. This entry is focused more on teaching kids to read.

One big issue with graphics has to do with teaching words – both in terms of the memorization of sight words and the mastery of word meanings (vocabulary).

What role, if any, should pictures play in these lessons?

I know some people will get their backs up about the idea of having kids memorize words (there is a “science of reading”, after all).

Even with decodable text, there may be a need to introduce words kids won’t be able to sound out. An example of this is high frequency words with unusual spelling patterns like of or the.

Also, sometimes, to keep decodables interesting or comprehensible, some words are introduced that, though decodable, are not yet decodable by the kids at whom this text is aimed – instruction hasn’t yet introduced those patterns. Depending on grade level, time of year, and specific decoding curriculum, words like dinosaur, monkey, plane, garden, or soccer could require some teaching.

Whether the word is the or monkey, I hope publishers will be sure to use those words frequently (Hiebert, Martin, & Menon, 2005). There is no point in teaching a word that won’t be used often. Also, teachers should introduce such words prior to the reading, that way kids can focus on the decodable patterns that they’re supposed to be practicing with those decodable texts.

Obviously, we won’t use a picture with a word like the, but we might with monkey.

However, according to scads of studies, such pictures provide more distraction than support (e.g., Harzem, Lee, & Miles, 1976; Samuels, 1970).

We learn to remember and read words by looking at the words, that is by looking at the combinations of the letters of which the words are comprised (and that’s as true for those exception words as for those that share common patterns).

Six-year-olds are more interested in looking at pictures of monkeys than at the letters m-o-n-k-e-y. Consequently, when presented with word and picture, they peruse the graphic rather than studying the letter sequence. At best their attention is split, reducing the likelihood of learning.

If your aim is to build vocabulary knowledge however, the picture is a bit different (yes, an intentional pun, forgive me). For this, pictures can be beneficial. Studies show that providing a graphic representation of words – even of abstract words – can increase understanding and retention (e.g., Coyne, McCoach, Ware, Loftus-Rattan, Baker, Santoro, & Oldham, 2022).

It is cool to provide a picture or even video to illustrate words, but I’ve also long embraced the idea of having students translate words into graphics (literally and metaphorically) as recommended by Camille Blachowicz and Peter Fisher (2006).

If the point is to get students to understand the meaning of a word they don’t know, pictures can be a real help, while if the idea is to help them to read or remember the word, pictures distract. If you want both, start with using a picture to help define the word and then cast it aside so the kids can focus on the letter sequence.

What about reading comprehension?

There are a slew of studies showing that readers comprehend better with illustrations (Aukerman & Chambers Schuldt, 2016; Beveridge & Griffiths, 1987; Hayes & Henk, 1986; Newton, 1995; O'Keefe & Solman, 1987; Sar?, Ba?al, Takacs, & Bus, 2019).

This is especially true for younger kids (Greenhoot, Beyer, & Curtis, 2014).

However, in most studies you can’t tell why. Often these studies just seem to show that kids understand pictures better than words. The pictures aren’t necessarily boosting how well kids understand the prose. No, they seem to provide an alternative – an easier route – to the information.

Should I don my Mr. Know-it-All cloak and lecture you on the sin of teaching reading with illustrated stories?

I don’t think so.

If there’s a “Mr. or Ms. Know It All” on this topic, I haven’t been able to locate him/her.

The truth is there’s no persuasive theory about the specific role pictures should play in comprehension teaching. We know preschoolers often think it’s the pictures – not the print – that tell the story (Ferreiro & Teberosky, 1982) but as they become more sophisticated readers, they come to view illustrations as little more than secondary adjuncts to most print (Waddill, McDaniel, & Einstein, 1988).

We lack purchase on how to get from here to there.

We know kids prefer books with pictures, and that’s not nothing. There’s also a plethora of advice about the types of illustrations that capture kids’ attention: vibrant colors, cartoon-style illustrations, lively pictures, exaggerated features (big eyes, especially), whimsical properties, and so on (e.g., Hall, 2025). You know, kids are attracted by anything that looks like it escaped from Disney studios.

Nothing wrong with that. Pictures draw kids into books, and these motivational properties neither contribute to nor interfere with comprehension development.

What info should pictures provide and how should they connect to text, and most important, what should teachers do about it?

Studies show that illustrations can boost both literal comprehension and inferencing (Pike, Barnes, & Barron, 2010). When pictures aren’t apt, they may lead to misunderstandings – they sometimes mislead kids as to what a text has to say.

There are different notions about the role pictures may play in comprehension.

One idea, dual coding theory (Pavio, 1971) claims we develop two systems for processing information – one dependent on linguistic codes and one on visual codes: words and pictures. Memory for information is heightened when learners connect the two channels – for instance, seeing the word “dog” and consequently thinking of its visual representation.

In that scheme, you want to develop lots of alternative representations. Learning can be gained from pictures or words but feeding both channels simultaneously may support more thorough and accessible memories.

Somewhat different insights may be drawn from Walter Kintsch’s theory of comprehension (1998). He claims learning is more about developing complete and coherent representations of events and experiences. The theory focuses on verbal learning, but it’s fair to say that young children may struggle to develop those coherent wholes when relying only on verbal information.

When it comes to reading, kids are doing more than just figuring out how to replace oral messages with written ones. They are simultaneously constructing their systems of cognition. Pictures may add a concreteness to verbal experiences making it easier – sometimes even making it possible – to form a coherent understanding.

Kids are not just replacing the words with the pictures during comprehension but they are using the pictures together with the words to construct a complete and coherent representation of meaning (Davis, Schrodt, & Lee, 2024; Lesgold, de Good, & Levin, 1977; Seger, Wannagat, & Nieding, 2021; Terry & Howe, 1988; Waddill, McDaniel, & Einstein, 1988).

Those theories don’t have much to say about criteria for good illustrations. They may, however, tell us something about what we could do with those pictures.

I think we should involve kids in more thorough analyses of the illustrations, evaluating the different information sources. What do the words tell you about the character or the event that the pictures don’t? And vice versa.

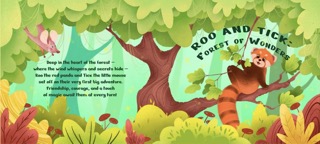

For example, let’s think about that for this short piece of illustrated text (from the gifted Kyrgyz illustrator, ??????? ???????, https://www.behance.net).

Both the picture and the words tell us this is a forest, and they disclose that the characters are a red panda, and a little mouse who are friendly with each other.

If you don’t know what a forest, red panda, or mouse are, then the pictures might serve as useful graphic definitions.

I’d ask boys and girls what a forest is, and if they knew, then we’d look at the picture to see if the illustrator got it right. If they didn’t know, then we’d use the picture as part of the definition. Also, kids might not know what a panda or a mouse look like, and it would be worth asking them, “Which one is Roo and which one is Tick?”

The words also carry important information that the pictures fail to – these animals are about to go on their first adventure together, and this adventure will involve friendship, courage, and magic. The picture shows their friendship (I think they’re smiling at each other), but it says nothing about courage or magic, or even that their friendship will matter somehow in their upcoming adventure. Nor does it tell their names, Roo and Tick.

On the other hand, the words are silent about how happy these animals are, nor do they mention that they can climb trees. The words tell us that there’s a forest, but it says nothing about the trees in that forest. Not only do these trees have leaves and branches, but vines, too (Tick is holding onto a vine, I think).

One difference between the picture and the words is how the mouse is characterized. The text says he’s little, but in the graphic, he seems almost as big as Roo – that would be a very big mouse. That’s one of those differences between text and picture.

The point of exploring such ideas in a discussion is to get kids exploring both the verbal and pictorial codes and their relationship (Pavio), and to use both together – along with prior knowledge – to develop a more complete and coherent representation of this story (Kintsch).

Advocates for the importance of knowledge in comprehension sometimes make it seem like the point of schooling is the accumulation of lots of random trivial facts, the kind of thing that can win you a lot of money on a quiz show. They may make it seem like lists of cultural information are the key to sound comprehension.

I don’t think it really works that way.

That’s why a story like this one can be so valuable, despite it being a fictional talking animal kind of yarn. Kids not only may gain factual information (about forests, mice, and red pandas) and cultural information (the natural darkness and wildness of forests can seem magical and mysterious), but they may also learn how these elements combine into coherent, meaningful memories – you know, learning.

Kids have difficulty doing that just with words, so the combination of verbal and graphic information matters.

Over time, as kids get better at that process – they need fewer pictures and more words.

Comprehension and learning to comprehend are different, but interdependent. Taking kids through that process repeatedly with a range of factual and fictional texts can provide them with processes and insights into how one goes about developing coherent representations. That’s kind of a reading strategy.

However, when we develop such representations, we employ past representations stored in our memories. We are inputting not only lots of those cultural touchstones (e.g., 1776, revolution, George Washington), but also coherence schemas (e.g., adventure stories, conflict, pride) that help us to organize those facts into something more substantial. That’s where prior knowledge comes in, and why we want kids to learn more than how to process text when we are guiding their reading.

Pictures may initially compete with the words in comprehension, but they’re essential for helping kids to gain coherent representations of what they read. The trick is neither to avoid the pictures nor to allow them to overwhelm the words. One of the things that can be accomplished during shared and guided reading is to show kids how to combine pictures and words to develop coherent representations, and then to wean them from the pictures over time.

Get the picture?

References

Aukerman, M., & Chambers Schuldt, L. (2016). “The pictures can say more things”: Change across time in young children's references to images and words during text discussion. Reading Research Quarterly, 51(3), 267-287. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.138

Beveridge, M., & Griffiths, V. (1987). The effect of pictures on the reading processes of less able readers: A miscue analysis approach. Journal of Research in Reading, 10(1), 29-42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.1987.tb00280.x

Blachowicz, C. L. Z., & Fisher, P. (2006). Teaching vocabulary in all classrooms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Coyne, M. D., McCoach, D. B., Ware, S. M., Loftus-Rattan, S., Baker, D. L., Santoro, L. E., & Oldham, A. C. (2022). Supporting vocabulary development within a multitiered system of support: Evaluating the efficacy of supplementary kindergarten vocabulary intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(6), 1225-1241. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000724

Davis, T. D., Schrodt, K., & Lee, S. (2024). An exploration of the impact of quality illustrations in children’s picture books on preschool student narrative ability. Reading Psychology, 45(7), 639. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2024.2351480

Ferreiro, E., & Teberosky, A. (1982). Literacy before schooling. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Greenhoot, A. F., Beyer, A. M., & Curtis, J. (2014). More than pretty pictures? how illustrations affect parent-child story reading and children's story recall. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00738\

Hall, L. (2025). The power of pictures. How book illustrations boost early literacy. Bloomington, IN: Literacy from the Start, Indiana University.

Harzem, P., Lee, I., & Miles, T. R. (1976). The effects of pictures on learning to read. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(3), 318-322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1976.tb02328.x

Hayes, D. A., & Henk, W. A. (1986). Understanding and remembering complex prose augmented by analogic and pictorial illustration. Journal of Reading Behavior, 18(1), 63-78.

Hiebert, E. H., Martin, L. A., & Menon, S. (2005). Are there alternatives in reading textbooks? An examination of three beginning reading programs. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 21, 7-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560590523621

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. Cambridge University Press.

Lesgold, A. M., de Good, H., & Levin, J. R. (1977). Pictures and young children's prose learning: A supplementary report. Journal of Reading Behavior, 9(4), 353-360.

Newton, D. P. (1995). The role of pictures in learning to read. Educational Studies, 21(1), 119-130. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569950210109

O'Keefe, E. J., & Solman, R. T. (1987). The influence of illustrations on children's comprehension of written stories. Journal of Reading Behavior, 19(4), 353-377.

Pike, M. M., Barnes, M. A., & Barron, R. W. (2010). The role of illustrations in children’s inferential comprehension. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 105(3), 243-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2009.10.006

Samuels, S. J. (1970). Effects of pictures on learning to read, comprehension, and attitudes. Review of Educational Research, 40(3), 397-407. https://doi.org/10.2307/1169373

Sar?, B., Ba?al, H. A., Takacs, Z. K., & Bus, A. G. (2019). A randomized controlled trial to test efficacy of digital enhancements of storybooks in support of narrative comprehension and word learning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 179, 212-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2018.11.006

Seger, B. T., Wannagat, W., & Nieding, G. (2021). Children’s surface, textbase, and situation model representations of written and illustrated written narrative text. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34(6), 1415-1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10118-1

Terry, W. S., & Howe, D. C. (1988). Effects of incidental pictorial and verbal adjuncts on text learning. Journal of General Psychology, 115(1), 41-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1988.9711087

Waddill, P. J., McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (1988). Illustrations as adjuncts to prose: A text-appropriate processing approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 457-464. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.4.457

LISTEN TO MORE: Shanahan On Literacy Podcast

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.