A slew of letters seeking ideas on disciplinary literacy.

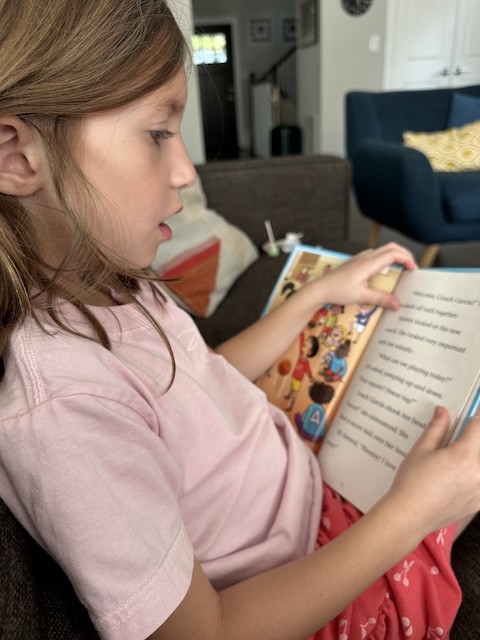

Teacher 1: The Common Core highlights that every teacher is a reading and writing teacher in their discipline. I think this idea is important in combination with the best practices for content area learning. My main interest in this is based on helping students who struggle to learn to read in early grade levels, and, as a result, can quickly get behind when "reading to learn" in the secondary grades.

Teacher 2: What is the place of disciplinary literacy in elementary school? I am also aware of the work of Nell Duke and the importance of informational text with young children as well as the significance of teaching academic vocabulary and scaffolding its use by the children.

Teacher 3: I very much like your explanation of Content Literacy vs. Disciplinary Literacy. With this in mind, how would you best support kindergarten-first grade teachers in the area of Disciplinary Literacy? Non-fiction informational texts, read alouds, inquiries, academic vocabulary, learning to read charts, photos etc. ...The ways to scaffold Disciplinary Literacy are much more clear to me as the children move up the grades.

Teacher 4: What would you say are some current best practices for secondary content area literacy?

Shanahan responds:

One hears the term disciplinary literacy a lot these days. That’s because the Common Core standards (CCSS) address the teaching of disciplinary literacy (as do non-CCSS states like Texas and Indiana).

Of course, the term is often misused. Disciplinary literacy is based upon the idea that literacy and text are specialized, and even unique, across the disciplines. Historians engage in very different approaches to reading than mathematicians do, for instance. Similarly, even those who know little about math or literature can easily distinguish as science text from a literary one.

Fundamentally, because each field of study has its own purposes, its own kinds of evidence, and its own style of critique, each will produce different texts, and reading those different kinds of texts are going to require some different reading strategies. Scientists spend a lot of time comparing data presentation devices with each other and with prose, while literary types strive to make sense of theme, characterization, and style.

The idea of teaching disciplinary literacy is quite different from the long promoted content area literacy teaching. The latter has often championed the disciplinary literacy notion, but the result has been an emphasis on general comprehension skills and study skills, rather than apprenticing young readers into reading like disciplinary experts. K-W-L, three-level guides, Frayer model, 4-squares, etc. are all great teaching tools—they can enhance kids learning from text, but you are unlikely to find chemists or historians who use those approaches in their work. Thus, content area reading aims to build better students, while disciplinary literacy tries to get them to grasp the ways literacy is used to create, disseminate, and critique information in the various disciplines.

This can get pretty confusing. Educators have a tendency to latch onto new terms without developing much of an understanding of them. These days many teachers think disciplinary literacy is just the cool new term for content area reading. Even some “scholars” are playing this game; grabbing onto family resemblances and seeing identical twins.

For example, Cyndie Shanahan and I studied chemists and learned the key information that they looked for when reading chemistry text and some of the techniques they used for making sense of that information. They even provided us with cogent explanations of why their approaches were beneficial, given the purposes of their inquiry and the nature of their texts.

We turned that into a method that chemistry students could use to summarize information in a chemistry-centric way. Some “scholars” decided such charting made disciplinary literacy the same as content area reading (since it often recommends charts, too), ignoring that the categories of disciplinary-specific information were the essential element, and not the piece of paper on which the kids were recording the information (Dunkerly-Bean & Bean, 2017).

Not surprisingly, since disciplinary literacy is a relatively new thing for schools, there is a flood of questions about it. And, because the research is lagging classroom demand, there is only a trickle of research-based answers to provide. Much of what O will write here will be based on my own personal experiences (teaching and co-teaching middle school and high school classes in various disciplines).

So what are the big issues in implementing disciplinary literacy?

First, reading has to be a big part of students’ disciplinary classes. I can’t think of anything more fundamental. If there are not real reasons to read in these classrooms, then there is no reason to teach disciplinary literacy or for kids to try to learn it. I do not believe that teachers of biology, algebra, American History, British Literature, economics, or any other subject in the curriculum should be deterred from teaching their subject matter. But part of that teaching should come through text.

What too many teachers do is to seek ways to avoid text. A biology textbook is hard to read, 15-year-olds struggle with it, so teachers present the pertinent information some other way: Powerpoint lectures, dumbed-down study sheets, etc. Those teachers often tell me that students have the option of reading—though why they would, given that all the test answers are provided fully digested, I can’t imagine.

Even math classes should include reading. I don’t mean story problems, though they have their place. I mean that kids should be reading theorems, problem explanations, formulas, proofs, and whatever mathematical information is appropriate. “But my students aren’t good readers?” I get it… and, yet, it is hard to see how avoiding math reading could possibly improve that situation.

In the elementary grades, making sure that kids are reading about geography, economics, history, culture, biography, environmental science, life science, physical science, music, art, and current events is really important. Building kids’ stores of knowledge in those areas and giving them practice dealing with that kind of language and content is imperative. Stories are great, but a narrow diet of stories alone can make you sick.

Second, if students are to read, there needs to be text… disciplinary appropriate text. That means in a history class it is essential students be given opportunities to pore over conflicting evidence and alternative points of view. That doesn’t mean that history textbooks have no place, only that students need chances to evaluate primary and secondary texts, too.

Science reading is less about alternative perspectives and more about accurate information carefully grounded in the observations and experiments that identified it. Accordingly, science information tends to be expressed in a multiplicity of forms (e.g., prose, tables, charts, formulae, photos), often within the same account—in part this is done because of the inadequacy of language to precisely summarize findings.

Students need opportunities to work with these alternative forms and to see more than science textbooks (not for alternative information, but to see how scientists report their findings). I taught a group of high-schoolers to read Watson & Crick’s landmark report of their discovery of the structure of DNA. Man it was tough slogging—for them and for me, but we got there, and the kids were enthusiastic about results (they asked their real teacher if they could do more of that).

A counter-example. Last year, I was co-teaching some math classes. The math textbook had been written purposely to place as little reading demand on students as possible. The math book was largely a collection of math problems, without explanation (the teachers capably provided that). That book not only failed to provide kids with opportunities to read math, but the parents hated it because if their children didn’t understand the math, they couldn’t help them to figure it out.

Elementary textbooks and tradebooks often report content information, but they rarely do so from a disciplinary perspective. Historical accounts tend to tell stories rather than revealing controversies, disagreements, or the use of evidence. Science accounts often provide terrific explanations of scientific phenomena, but without much revelation of how this information came into being. And, how often are younger children exposed to literary criticism as opposed to literature.

My point isn’t necessarily that such texts should be included in the elementary curriculum, but if they aren’t then it doesn’t make a lot of sense to try to engage them in disciplinary approaches. Those only make sense when one is reading works that have a definite disciplinary cast or when one is engaged in disciplinary inquiry that includes reading. Until such texts become available—and that could be earlier, but often isn’t until middle school—satisfy yourself with exposing students to lots of informational texts and the knowledge they represent.

Third, disciplinary classes should have a deep dedication to imparting the content of the subjects to students, including information about the nature of inquiry in those fields. What does it mean to work as a historian, scientist, geographer, mathematician, or literary critic? What do they read and why? How do they report their results? What constitutes evidence in their field of study? What does criticism look like?

Some curriculum experts believe that means students have to be engaged in inquiry themselves in the various fields. I like that idea, and it often makes sense. Labs are common in high school sciences, though the lab reporting too often seems distant from how scientists report their findings. In history classes, it has become much more common to see students reading text sets that expose them to conflicting accounts (e.g., History Scene Investigations), so kids can weigh in on contested issues in history.

But inquiry is not without problems (I’ve yet to see a text set that shows students how historians take into account the economic or geographic antecedents of historical events).

Inquiry can be cumbersome and time consuming; it always requires a wise balance of content coverage and the appreciations to be derived from hands-on investigation. And, there are disciplines that simply aren’t amenable to inquiry—math is particularly knotty in this regard (making me wonder if math isn’t different than the other disciplines in that having students acting like nascent mathematicians might not have the same payoffs as trying to read like scientists or literary critics).

In the elementary school, it makes great sense to emphasize learning as well, and there will be times when inquiry is the way to go. (There might be wonderful benefits for writing reports of various types, but such reports tend not to be disciplinary by nature—a report on photosynthesis written by a fourth-grader is going to be more about finding facts in various sources than about reporting scientific information in the way a scientist would).

However, again, that doesn’t mean there is no place for such work in an elementary classroom. Engaging students in trying to solve various kinds of quantitative problems and writing about these explorations makes a lot of sense. Having kids observing some natural phenomenon or conducting an experiment and reading about the phenomenon understudy to combine this information coherently could be very powerful.

The point is that content and inquiry are the point—and that disciplinary literacy should emanate from the demands of that content and inquiry. There will definitely be more opportunities at some levels than at others.

.jpg)

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.