Literacy Blogs

- All

- 3-cueing

- academic learning time

- academic vocabulary

- accommodations

- accountability testing

- Active View of Reading

- adolescent literacy

- afterschool programs

- alphabet

- amount of instruction

- amount of reading

- argument

- assessment

- auding

- author awareness

- automaticity

- balanced literacy

- beginning reading

- Book Buddies

- Book Flood

- challenging text

- classroom organization

- close reading

- coaching

- cohesion

- Common Core State Standards

- complex text

- comprehension strategies

- content area reading

- context analysis

- curriculum materials

- Daily 5

- decoding

- departmentalization

- DIBELS

- dictionary skills

- digital texts

- disciplinary literacy

- dyslexia

- early interventions

- effective teachers

- Emily Hanford

- executive function

- family literacy

- fingerpoint reading

- foundational skills

- graphic novels

- guided reading

- heterogeneous grouping of students

- homework

- improving reading achievement

- independent reading

- independent reading level

- informal reading inventories

- informational texts

- instructional level

- invented spelling

- jigsaw instruction

- knowledge

- leadership

- learning disabilities

- Lexiles

- linguistic comprehension

- listening comprehension

- literacy charities

- literacy policy

- literary interpretation

- main idea

- morphology

- motivation

- narrative text

- National Early Literacy Panel

- nonsense words

- oral language

- oral reading fluency

- paraphrasing

- Pause, Prompt, Praise (3P)

- personalized learning

- phonemes

- phonemic awareness

- phonics

- press and media

- principals

- prosody

- Readers' Workshop

- reading comprehension

- reading disabilities

- reading intervention

- reading levels

- reading models

- Reading Recovery

- reading research

- reading skills

- reading strategies

- reading to children

- reading wars

- reading-writing relations

- remedial reading

- rereading

- Response to Intervention

- Scarborough's Rope

- science of reading

- seatwork

- semantics

- sentence comprehension

- sequence of instruction

- set for consistency

- set for variability

- shared reading

- shared reading

- sight vocabulary

- simple view of reading

- Simple View of Reading

- small group instruction

- social studies

- sound walls

- Special Education

- speech-to-print phonics

- spelling

- stamina

- summarizing

- Sustained Silent Reading

- syllabication

- syntax

- syntax

- testing

- text complexity

- text interpretation

- text reading fluency

- text structure

- theme

- think-pair-share

- trauma

- visualization

- vocabulary

- word walls

- writing

- zone of proximal development (ZPD)

How Should We Plan Reading Comprehension Lessons?

Teacher Question As my teachers continue learning together about text-centered planning, I would love your help with a quick reflection. When you sit down to plan a unit: How do you decide which comprehension standards the anchor text naturally requires? What steps do you take to analyze the text before identifying standards? How does the text guide the sequence of lessons and questions? Shanahan Responds: I’ll answer your questions. But before I do, let me try to fend off some of the defensive comments my response is sure to elicit. First, yes, I understand that teachers are busy and can’t design every lesson themselves in depth. No, I ...

Are We Teaching Too Much Phonics?

Teacher question: I saw that Mark Seidenberg was complaining that there is now too much phonics instruction. What do you think of that? Shanahan replies: I have great respect for Dr. Seidenberg’s work but have long been critical of his tendency to ignore research on reading instruction. In his wonderful book, he argues for the teaching of phonics with barely a nod to any of the studies of phonics teaching. Being an experimental psychologist, he was convinced of the value of phonics based on computer simulation studies. I, being a teacher, am more persuaded of the value of phonics because of the many studies ...

What Are the Best Fluency Learning Targets? I Think My School is Overdoing It

Teacher question: I am a literacy interventionist at an elementary school, and we use DIBELS for our progress monitoring. While I recognize the value of DIBELS as a screening tool, I have concerns about the appropriateness of the current fluency benchmarks my school has adopted. I have found some research that identifies fluency goals calibrated to reading comprehension. Studies by O'Connor (2017) and Cogo-Moreira et al. (2023) identify specific words-per-minute benchmarks to establish a cut-off point for reading speed and accuracy to obtain minimum values for comprehending texts. These wpm goals are much lower than our fluency goals. If the ultimate ...

When Should Reading Instruction Begin?

Blast from the Past: This entry first dropped on October 26, 2019, and was reissued on January 24, 2026. The only change is an update to the NAEYC statement (it was in draft form when originally cited). Teacher question: What does research say about early literacy and when to begin? I am aware that kids may reach the stage of development where they're ready for reading at different times. What does the research say about the "window" for when a kid can learn to read? What are the consequences if they haven't started reading past that time? Shanahan response: Oh, fun. The kind of ...

What We Talk About When We Talk About Reading Curriculum

Erasmus wrote that “every definition is dangerous.” His abhorrence for the sharp definition was due to a fear of dogmatism. I’m no Erasmus but I’d say, “let’s risk it.” Experience tells me that weak definitions can do even more damage. Our vague defining leads to misunderstandings and undermines sound decision making. If you aren’t sure what “balanced literacy” or “science of reading” mean, how can you deliver –- or avoid delivering — the appropriate pedagogy? In education, we don’t define well. Often we adopt nomenclature without definition (“balanced literacy” and “science of reading” are good exemples of that) and other times we subtly ...

What Teachers Need to Know about Sentence Comprehension Revisited

Blast from the Past: This blog first posted on August 13, 2022. There was no incident that led me to repost this on December 13, 2025, just my own sense that it would be a good idea to revisit this much neglected aspect of teaching students to understand text. Originally, there was no podcast of this and now there is, and this updated version includes both a link to that podcast as well as to the original blog that elicited 23 thoughtful comments. What Teachers Need to Know about Sentence Comprehension Awhile back, I posted an opinion piece calling for the explicit ...

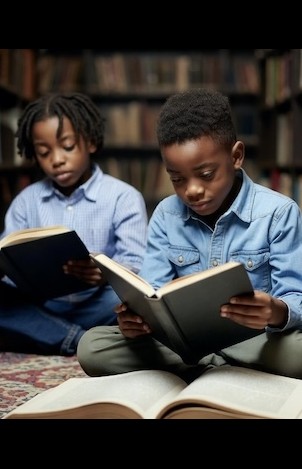

Literacy Charities for 2026

The whole point of Shanahan on Literacy is to encourage and support higher reading achievement. Towards that end, each year I recommend the highest rated literacy charities. I recognize that, like me, you have deep commitments to children’s reading success. That’s why it makes sense to include in our charitable giving organizations that distribute books to kids or that support their reading education in other ways, too. Annually, I consult Charity Navigator (U.S.) and Charity Intelligence (Canada) to identify the top-rated literacy charities (4-stars in U.S., and 5-stars in Canada). What that means is that you can be sure that every one ...

Won’t Challenging Texts Discourage Young Readers?

Teacher Question: I know you say students learn more when taught with grade level texts than texts at their reading levels. That may be true but won’t frustrating kids like that make them hate reading? Shanahan responds: I don’t want to undermine anybody’s motivation or love of reading. Though reading experts have long labeled some texts as “frustration level,” I hope you won’t take that moniker too literally. To be fair, your concern does seem justified according to some studies. For instance, middle school students say that when texts are difficult, their interest declines (Wade, 2001). Correlations among reading comprehension and affective variables like ...

Whole Books or Excerpts? Which Does the Most to Promote Reading Ability

Over the past few weeks, I’ve had several inquiries about the importance of whole book reading within reading instruction. And no wonder. Social media has been aflame with righteous claims about this purported and purportedly damaging shift to having students read excerpts within reading lessons rather than taking on whole books. I say “purported” because the claim seems to be that in the past teachers were teaching their kids to read books, and now they aren’t. I’ve been around quite a while, and I don’t remember the past that way. I say “purportedly damaging” because the idea that teaching reading with excerpts ...

Don’t Confuse Reading Comprehension and Learning to Read (and to Reread)

Blast from the Past: This piece was first published on May 7, 2022, and was republished on October 25, 2025. The original posting explained the distinction between a comprehension effect and a learning effect. Recently, I published a book on “leveled reading” that addresses this difference more thoroughly (Shanahan, 2025). The failure to make a discernment between these two outcomes has led to many pedagogical failures. Given that, I thought this to be a good time to sharpen the points made here, providing greater clarity and some background information about the source of this unfortunate misunderstanding, along with some specific ...